Timi Edwin was only 10 years old when her peers started to taunt her for having a big stomach and no breasts. They called her all sorts of names, which made her sad. “I felt bad, insignificant,” Timi told channelstv.com. “I felt like I shouldn’t have been born. And it affected my psychology because I developed low-self esteem, which affected my studies.”

In university, she was advised to pull out of school because she was always falling ill.

When she started dating, most of her partners acted like they were doing her a favour. One engagement fell through after two years.

At some point, Timi wished for death.

But relying on support from her mother and God, she resolved that sickle cell disease would not define her.

Today, Timi has degrees from Covenant University and Business School Netherlands. She also has more than a decade of experience working in the corporate world and is the founder and CEO of CrimsonBow Sickle Cell Initiative, a nonprofit that aims to enlighten more Nigerians about sickle cell disease and provide emotional and medical support to patients.

With support from the Ford Foundation and other donors, CrimsonBow, since 2017, has organised community outreaches in rural communities where people are sensitised and tested for the disease. CrimsonBow also holds a monthly clinic where drugs and emotional support are provided to patients. Thousands have benefited. “I am extremely fulfilled,” Timi said.

Sickle cell disease, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), is a major genetic disease where the normal round shape of red blood cells become like crescent moons, leading to blood clots which can cause extreme pain in the back, chest, hands and feet.

A stem cell transplant, a procedure that requires a donor, is expensive, emotionally exhausting and carries fatal risks, is the only known cure.

The disease is prevalent in Nigeria, perhaps more than anywhere in the world.

About 30 per cent of the Nigerian population are carriers of the sickle cell trait. And almost three per cent of Nigerians are living with the disease.

It is considered to be the most common genetic disorder in the country, but testing is not available to the vast majority of infants, leading to thousands of deaths every year.

Early detection is key because most sickle cell patients die during the first five years of life.

Approximately 50% of deaths occur during the second six months of life, according to one study.

Lekmark Tyoden was one of those who made it through to adulthood.

“It has been a journey that is tough,” he said. “It is associated with painful episodes. I lived with it through childhood. And a lot of my activities were disrupted, including schooling.

“I used to love playing football, but I have to watch my limits. If it becomes too strenuous, it can be a source of trigger.”

As a child, he too was stereotyped.

“People called me a weakling, a sickler,” Lekmark, who is now a clinical psychologist in Jos city, said.

“Some say because you are living with sickle cell, you cannot live above a certain age. And it is expected that you will die soon. Those kinds of statements can affect people psychologically. You have people who go into depression because of these forms of stigma. They isolate themselves, they have self-doubt.

“But we are capable of making contributions to humanity. We are capable of living.”

Controversial moves

In September, the Nigerian Senate passed a bill seeking to improve the prevention and management of sickle cell disease. It was a pivotal moment.

Chairman of the Senate committee on health, Yahaya Oloriegbe, said the bill “will strengthen existing structures” to eliminate the disease.

According to a copy of the bill obtained by channelstv.com, it will empower the Ministry of Health to accredit reputable public and private hospitals which will offer free genotype testing, counselling and treatment.

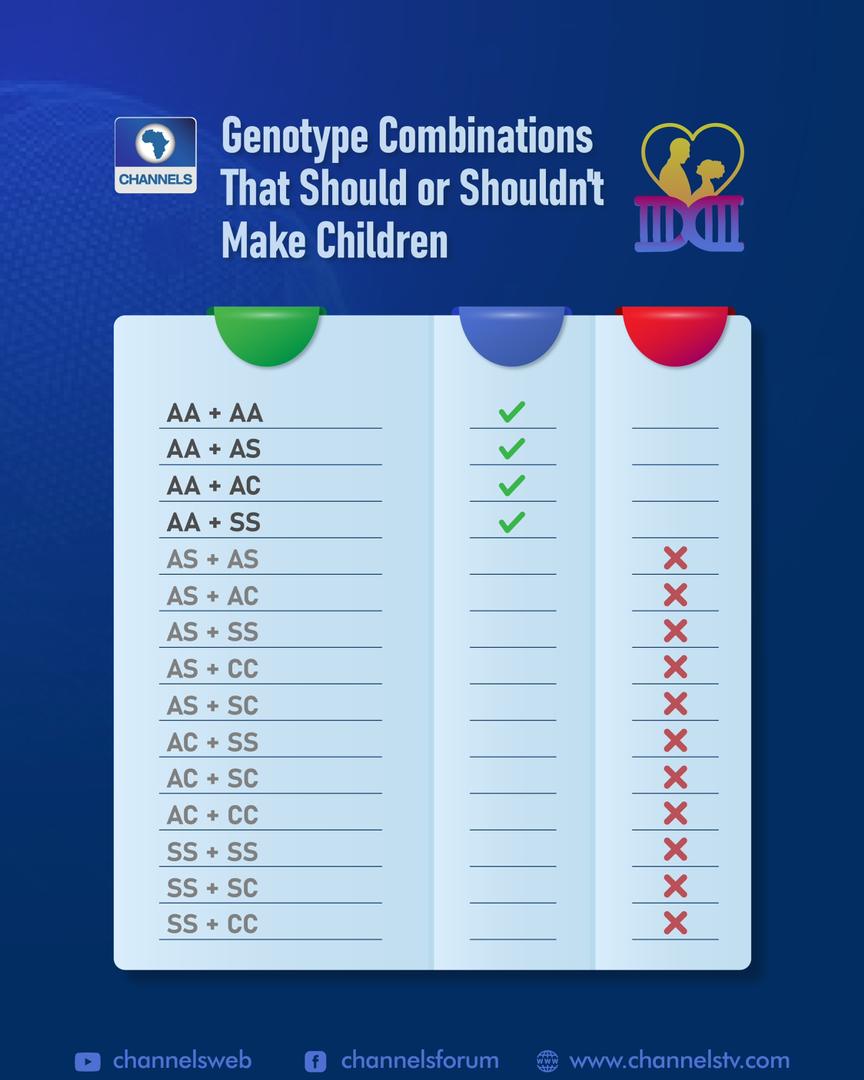

The bill, which was originally sponsored by Senator Sam Egwu of Ebonyi, also contains clauses that actively seek to dissuade carriers of the sickle cell gene from getting married and birthing children. This stems from an unproved belief that ensuring two carriers of the sickle cell gene do not produce children may, in a generation or two, wipe out the disease.

But these clauses have been criticised by Annette Akinsete, a public health physician and National Director at the Sickle Cell Foundation Nigeria.

“It’s very simplistic,” she said in an interview with channelstv.com. “It’s not as simple as it appears in real life. We have to base whatever we do on science. What is the scientific evidence?

“On the contrary, there is scientific evidence that when you compel or force people who are interested in marrying each other from not doing so because of sickle cell disease, it leads to a lot of dislocation of relationships. They go on and marry other people, but they don’t bring their complete selves into their current relationship.

“Also, it’s a human rights issue. You have no right to compel other people to go along with your belief.”

In 1995, the Military Administrator of Oyo State proposed a punitive edict aimed at prohibiting marriages between carriers of the sickle gene, but it was later deemed to be unconstitutional and a contravention of the human rights charter, to which Nigeria is a signatory.

“The reality . . . is that enforced selective mating of couples has never been shown anywhere in the world to have reduced the incidence of any inherited disorder,” said a paper by Professor Olu Akinyanju, a Hematologist and Founder of the Sickle Cell Foundation Nigeria. It was attempted by the Church in Cyprus for the control of thalassaemia but led to “increased anxiety and stigmatisation of affected persons and healthy carriers of the gene.

“This, in turn, led to widespread denial and falsification of haemoglobin genotype results among carriers who wanted to marry each other.

“What the Church in Cyprus now does is to ensure that all couples have been counselled on thalassaemia before marriage.”

Akinsete has proposed a similar revision for the Nigerian sickle cell bill.

“What you need is excellent counselling practices,” she said. “And that goes hand-in-hand with testing. So when you test early, we are targeting young people in elementary, primary, secondary and university; long before they get into relationships, they already know what their genotype is. So it’s not when they are ready to walk on the aisle, you begin to do tests. That’s pretty late. At that point, they are already invested in each other. We are asking for a bill that speaks to early diagnosis.

“Couples who come forward for counselling, even those who are near marriage, 80 per cent of those that are properly counselled will not go along. It’s the 20 per cent that will decide to proceed. So, those 20 per cent, you should give them the available options. There is what you call prenatal diagnosis, so they can determine the genotype of the foetus. And sickle cell is getting better and better treated globally; we were just talking about clinical trials for new drugs.

“Then there is what we call preimplantation genetic diagnosis. It’s done through IVF. That is also fraught with a lot of ethical, sometimes religious considerations. I’m Catholic and in catholicism that amounts to murder. But these are still options that are available. There is also adoption.”

Living with the pain

Bunmi Eunice, 31, wasn’t diagnosed with sickle cell disease until she was seven years old, after suffering from waist pain for over two years.

“I would scream; it was so uncomfortable,” she said of the waist pain. Then she was admitted to the hospital and tests revealed her red blood cells were sickle-shaped.

“I used to miss school for weeks; and when I resume everybody would be like ‘sorry’; and nobody must flog you and you weren’t allowed to do anything strenuous,” she said. “I felt different from everybody else. I felt like I couldn’t do what others could do. But I also knew it was for my own good.”

Over the years, she has learnt to live with the disease.

“I have grown to a place where I can take care of myself,” Bunmi, now a graduate of the University of Benin, told channelstv.com. “My crises have reduced. I don’t have any other underlying issues apart from sickle cell disease. And I take care of myself and observe my medication – Folic Acid, B-Complex, Vitamin C and multivitamins. I drink a lot of water and eat well, including a lot of fruits.

“Recently, I have been exercising and found out it was of help; but nothing so strenuous; something I know my body can cope with. I also take painkillers. I go for blood tests to check the level of my PCV (Packed Cell Volume) once I don’t feel good, especially when I’m done with my period.”

But a lot of sickle cell patients are not so lucky due to a multitude of factors, including genetics, quality of healthcare and emotional support. The behaviour of sickle cells can lead to stroke, chest pain and difficulty in breathing, hypertension, damage to organs such as the kidneys, liver and spleen. Others include blindness and leg ulcers. In men, sickle cells can lead to painful, long-lasting erections which can lead to impotence over time. And pregnant women with sickle blood cells are more likely to experience miscarriage or premature birth.

“It’s overwhelming,” says Eunice. “When I am down medically, I get necessary treatment as fast as I can; and psychologically, I just try to be happy. All over your body, you are feeling pain; you can’t even get up, you can’t even breathe properly. Someone who doesn’t have it does not really understand. The degree of pain is like a hundred raised to the power of 10.

“But it’s not the end of the world. You just have to keep going. Because when you start feeling depressed, you start degrading your self-worth. And it can lead to suicide. People in the world have other challenges; there is cancer, Covid, HIV/AIDS. Sickle cell disease is not the worst.”

A permanent cure?

Ebenezer Mathew, 20, thought he would always live with excruciating pain and countless trips to the hospital. But in 2013 he received a stem cell transplant in Benin-City and his genotype changed from SS to AA.

“The difference is much,” Mathew, who is now studying to be an anesthesiologist, told channelstv.com. “I don’t fall sick again. I don’t think I have been admitted to a hospital since then. The surgery changed my life.”

Stem cell transplant is the proven way to permanently cure sickle cell disease, but it is out of reach for millions of Nigerians affected due to its cost implications, according to the surgeon who operated on Mathew, Professor Nosakhare Bazuaye.

“An average transplant will cost close to about $20,000 (N10 million),” Professor Bazuaye said in an interview. “Transplants in low-resource countries like India will cost about $25,000. But in Europe, it will cost about $250,000, and that’s millions of naira.

“But we can do it in Nigeria for between 10 to 15 million naira. Everything we use is in dollars; all the drugs are imported in dollars. Power is also a big problem. To run the centre, the patient is on admission for two to three months, we need to power the clinic for those months. And in a month, you spend over a million on power – diesel is very expensive. On average, for just power alone, you are spending over four million. Whereas in developed countries, power is usually available.

“And then you buy drugs again, and another four million is gone. And bed fees and other ancillary things like blood. So just the cost gulps more than N10 million. This is something we had hoped the government would come in fully, just like they do in India, and make it medical tourism. I get patients from Ghana and other West African countries. But it’s on a small scale. We only have four isolation rooms, whereas where I was training in Switzerland, we had over 30 isolation rooms. And we could do an average of 30 to 40 transplants in a month. In Benin-city, we can only do an average of two to three transplants in a month. How many Nigerians can also afford it?”

Professor Bazuaye is on record as the first doctor to perform a successful stem cell transplant in Nigeria, in 2011, at the University of Benin’s Teaching Hospital (UBTH). The patient was a five-year-old, Ndik Mathew. His blood was drained and replaced with that of his brother, which has no trace of sickle cell anaemia. To deliver a successful operation, UBTH ensured there was 24-hour electricity supply. He was also kept in an air-tight room in the Stem Cell Centre for months. The centre was powered by two industrial generators gulping up 60 to 100 litres of fuel per hour.

Over a decade after that operation, not much has changed in terms of power infrastructure or significant government intervention. After just three successful surgeries at UBTH, Professor Bazuaye and his team partnered with Celltek healthcare, a private facility in Benin City. At least 17 stem cell transplants have been carried out under that partnership.

“Right now, I’m Chief Medical Director in Igbinedion University Teaching Hospital,” Professor Bazuaye said. “We are trying to use a CBN facility to build an international transplant centre. We want to be able to do as many transplants and make it medical tourism.

“We are hoping, for example, that the wife of the governors can take it as part of their responsibility. If every wife of a governor sponsors one transplant a year, they would have sponsored 37 times four. That would go a long way. Most Nigerians cannot afford the transplant. But we are hoping that NGOs, the government, wives of governors can come in and make this thing as easy as possible.”

The case for early testing

Zainab Bagudu, now a doctor abroad, lost two aunts to sickle cell disease while living in Nigeria.

“My grandparents had eight to nine kids. I know two passed away from sickle cell before I was even born. And the other two, in their adulthood.”

She remembers the deaths as painful and now believes they may have survived for much longer if her grandparents had better access to information about the disease.

“It boils down to education,” Dr Bagudu said. “Even the politicians need to be educated.”

A huge proportion of sickle cell disease deaths in Nigeria occur in children under five. According to a recent study in the respected medical journal The Lancet, the disease contributed about six per cent of total deaths among under-five Nigerian children between 2003 and 2013. During this time period, the disease killed approximately 35,000 children every year. Most parents do not even know their children have the disease until tragedy strikes and explanations like witchcraft and bad luck are proffered.

Between 2011 and 2012, the Federal Ministry of Health initiated a plan to establish six special Millenium Development Goal (MDG) sickle cell centres across each geopolitical zone (Kebbi, Gombe, Nasarawa, Ebonyi, Lagos and Bayelsa). Each centre was equipped with a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) machine, used for diagnosing the disease. But by 2017, the number of newborn babies screened was fewer than 2,000 across the six centres, according to one study due to low budgetary allocation, inadequately trained personnel, expired reagents, limited availability of consumables, absence of mechanisms to collect samples from babies regularly and, of course, erratic power supply.

In 2020, the Consortium on Newborn Screening in Africa (CONSA), an initiative funded by the American Society of Haematology (ASH), was launched to screen 10,000 – 16,000 babies per year over the next five years in seven African countries, including Nigeria. Professor Obiageli Nnodu, a haematologist with 36 years of field experience, is coordinating the CONSA programme in Nigeria.

While the pilot CONSA programme will only cover a tiny fraction of all babies born in Nigeria, it aims to establish the value of newborn screening to the government.

Rather than invest in expensive equipment without adequate support facilities like in the past, Professor Nnodu has co-published a paper showing how a $2 test can be incorporated into existing immunisation programmes in primary healthcare settings. In an interview with channelstv.com, she said the Federal Government was in the process of formulating a policy that inculcates the $2 test, but it remains unclear how successful the nationwide execution will be.

“What we need is more education,” Professor Nnodu

said. “Sickle cell disease can be easily treated if newborn babies are tested early and are placed on medication.” She gave an example of two babies who tested positive for sickle cell disease at the beginning of the CONSA programme last year. While one set of parents refused to believe their baby had sickle cell since they looked healthy, the second set of parents quickly began the necessary line of treatment. The untreated baby died weeks later while the other baby has already celebrated a first-year birthday.

Keeping hope alive

“When people know their genotype, it will go a long way in reducing sickle cell cases in Nigeria,” Timi Edwin, whose organisation Crimsonbow had organised numerous community outreaches, told channelstv.com.

She hopes the government makes testing mandatory for all newborns and ramps up sensitisation about sickle cell disease across the country.

“Government has the machinery to create impact on a larger scale,” Lekmark, the clinical psychologist in Jos, said.

But, like Timi, Lekmark is not just waiting for the government. In Jos, he is part of a group that provides emotional support and medication to sickle cell disease patients and those who want to learn more about the condition.

“God has been gracious to me,” Lekmark said, about what keeps him going besides the support of family and friends.

“I have seen him come through for me. Developing that relationship with my creator also gives me a sense of purpose, that I have to keep living. He was the one that created me, he has a plan for me. I believe that so much. I know that I am not a coincidence. I carry that positivity in my mind.”